How to Prepare for Pediatric Procedures with Pre-Op Medications: A Practical Guide for Parents and Caregivers

Why Pre-Op Medications Matter for Kids

Going under anesthesia or sedation for the first time is scary-even for adults. For a child, it can feel like being pulled into a world they don’t understand. That’s why pediatric pre-op medications aren’t just a medical formality-they’re a critical tool to reduce fear, prevent trauma, and make the whole process safer. Studies from the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne show that using the right pre-op meds cuts postoperative behavioral problems by 37%. That means fewer nightmares, less clinging, and less crying after the procedure. Parents report higher satisfaction too-scores jumped from 6.2 to 8.7 out of 10 when proper medication protocols were followed.

But it’s not just about calming kids down. These medications help manage real physiological risks. Children have faster metabolisms, smaller airways, and less developed reflexes than adults. A simple mistake-like giving the wrong dose or letting a child eat too close to surgery-can lead to vomiting, aspiration, or even a failed procedure. That’s why hospitals follow strict, evidence-based guidelines. This guide breaks down exactly what you need to do, when, and why.

When to Stop Eating and Drinking

Fasting rules for kids are different than for adults-and getting them wrong is one of the most common reasons surgeries get canceled. The key is timing, not just cutting food out.

- No solid foods after midnight the night before for children over 12 months. This includes milk, yogurt, or even peanut butter on toast.

- Milk and formula can be given up to 6 hours before the scheduled arrival time at the hospital.

- Breast milk is allowed until 4 hours before the procedure. It empties from the stomach faster than formula.

- Clear liquids-water, Pedialyte, apple juice without pulp, or Sprite/7-Up-are okay up to 2 hours before surgery. This is shorter than the 4-hour rule for adults because kids digest liquids faster.

Many parents get confused about what counts as a “clear liquid.” Orange juice? No-pulp makes it not clear. Smoothies? No. Gatorade? Yes, if it’s the original flavor without added fiber or chunks. One Texas Children’s Hospital study found 28% of parents misunderstood this, and 15% gave their child orange juice, thinking it was fine. That’s a recipe for delay or cancellation.

Always double-check with your hospital. Some facilities have slightly different rules, especially for premature babies or kids with gastrointestinal conditions. When in doubt, call the pre-op nurse. It’s better to be overly cautious than to risk postponing the procedure.

Common Pre-Op Medications and How They Work

Not every child needs sedation before surgery, but most do-especially those under 6. The goal isn’t to knock them out, but to make them calm and cooperative. Three main medications are used, each with pros and cons.

Oral Midazolam

This is the most common. Given as a sweet liquid, it’s easy to swallow and works in 20-30 minutes. The dose is 0.5 to 0.7 mg per kilogram of body weight, capped at 20 mg total. It reduces anxiety, causes mild amnesia (so kids won’t remember the IV insertion), and helps them relax. Most kids fall into a drowsy but responsive state. Parents often say their child seems “like they’re in a happy dream.”

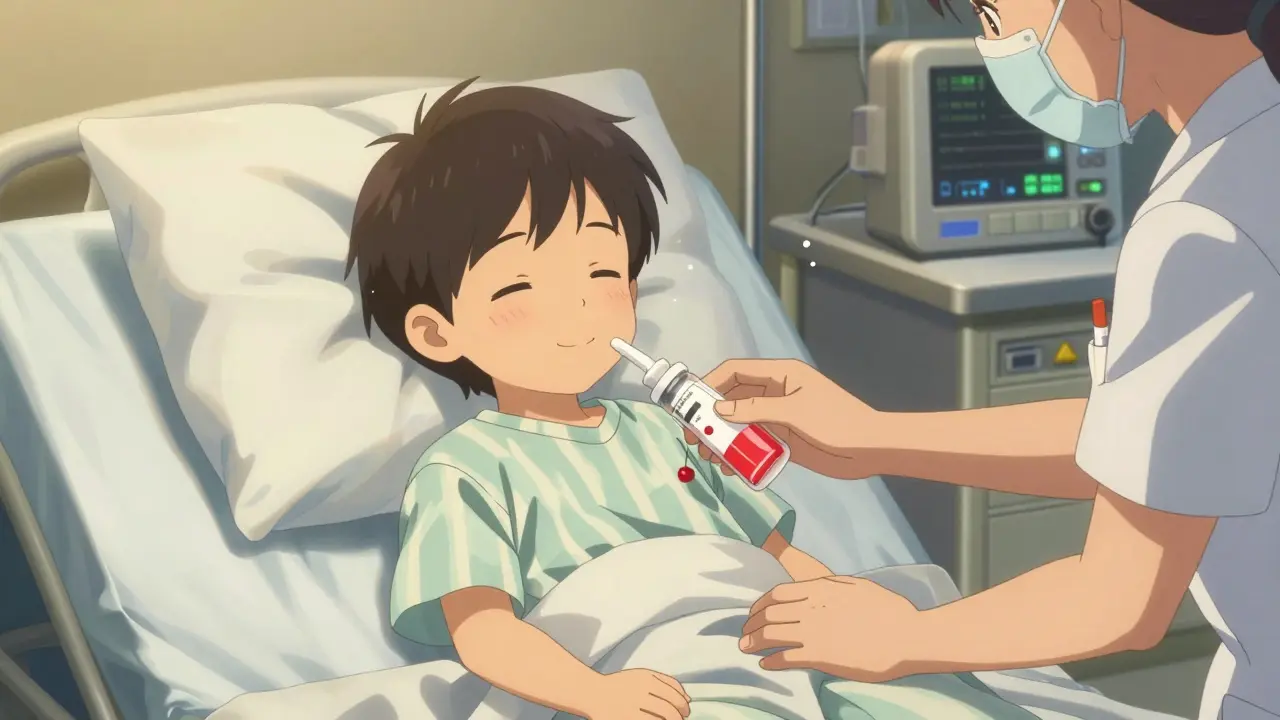

Intranasal Midazolam

For kids who won’t swallow pills or liquids, this spray goes into each nostril. Dose is 0.2 mg per kg, max 10 mg. It works faster-sometimes in 10 minutes-and is effective in 85% of cases. But 12% of children get nasal irritation or mild bleeding. If your child has a stuffy nose or adenoids, this might not be the best choice.

Intramuscular Ketamine

This is for the toughest cases: kids with severe anxiety, autism, or developmental delays who won’t cooperate with oral or nasal meds. Given as a shot in the thigh, it takes 3-5 minutes to kick in. It doesn’t make kids sleep-they enter a dissociated state where they’re calm but still aware. Anesthesiologists like it because it gives parents time to hold their child before the child “zones out.” The downside? About 8-15% of kids have emergence delirium-crying, thrashing, or confusion-when they wake up. That’s why it’s reserved for cases where other options have failed.

Important: Never give these medications yourself. They’re only administered in the hospital under supervision. Your job is to make sure your child takes the right one at the right time.

Special Medication Considerations

Many kids are on daily medications for conditions like epilepsy, asthma, or acid reflux. The rule? Don’t stop them unless told to.

- Antiepileptic drugs (like levetiracetam or valproic acid): Keep giving them with a sip of water on the morning of surgery. Stopping them can trigger seizures. A 2022 AAFP report found 32% of pre-op errors involved accidentally holding these meds.

- Proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) or H2 blockers (like famotidine): Keep taking them. They reduce stomach acid and lower the risk of aspiration.

- Asthma inhalers (albuterol): Use them as usual the morning of surgery. Children with uncontrolled asthma have a 40% higher risk of airway spasms during anesthesia. CHOP data shows compliance with this rule cuts bronchospasm incidents in half.

- GLP-1 agonists (like semaglutide or exenatide): If your child is on these for weight management or diabetes, stop them 1 week (semaglutide) or 3 days (exenatide) before surgery. These drugs slow stomach emptying and increase aspiration risk, especially in older kids.

Always bring a full list of medications-including dosages and times-to your pre-op appointment. Hospitals use a checklist called AAFP Table 3 to verify what can and can’t be continued. Don’t assume your pediatrician already told the surgical team. You’re the best advocate for your child’s routine.

What to Do If Your Child Has Autism or Special Needs

Children with autism, ADHD, or developmental delays are at higher risk for extreme anxiety and non-compliance. Standard protocols often don’t work. That’s why hospitals like RCH Melbourne have modified approaches.

- Start preparing early-48 hours before. Use social stories, videos, or picture cards to explain what will happen.

- Request a pre-op visit. Many hospitals let families tour the pre-op area and meet the anesthesiologist ahead of time.

- Ask about clonidine. This non-sedative medication (given 4 hours before surgery at 4 mcg/kg) reduces anxiety without causing drowsiness. RCH data shows 40% of children with autism need this adjustment.

- Bring comfort items: a favorite blanket, toy, or headphones with calming music. These reduce the need for higher doses of sedatives.

- Ask if the hospital uses distraction techniques like virtual reality goggles during IV placement. Some centers report up to 60% less anxiety with these tools.

Don’t be afraid to speak up. If your child has a history of trauma, sensory issues, or extreme resistance, tell the team. They’ve seen it before-and they’ll adapt.

What Happens in the Pre-Op Room

When you arrive, the nurse will check your child’s weight, confirm fasting times, and verify all medications. Then comes the premedication.

For oral midazolam: A nurse will give your child a small cup of sweet liquid. It might taste like cherry or grape. You’ll be asked to stay with your child for 20-30 minutes while it takes effect. Don’t rush them. Let them sit, read, or watch a video. Most kids become calm and cooperative-some even laugh.

For nasal spray: The nurse will gently spray one side, then the other. It doesn’t hurt, but some kids flinch. Hold them close and talk softly. Within minutes, their eyes will get heavy.

Monitoring starts immediately: A pulse oximeter clips onto their finger to track oxygen levels. Blood pressure is checked every 5 minutes. If they’re getting ketamine, they’ll be watched closely for breathing changes.

Parents are usually allowed to stay until the child is fully sedated. Then, an anesthesiologist will gently take them to the operating room. You’ll be reunited in recovery once they’re awake.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even with the best intentions, parents make errors. Here are the top 5-and how to dodge them.

- Not confirming clear liquids → Double-check with your hospital. Avoid anything with pulp, milk, or color.

- Stopping essential meds → Write down every medication and ask, “Should I keep giving this?”

- Waiting until the last minute → Start preparing 24 hours ahead. Set phone alarms for medication times and fasting cutoffs.

- Underestimating anxiety → If your child is terrified, say so. There are options beyond midazolam.

- Not bringing a full med list → Include vitamins, supplements, and over-the-counter drugs. Even melatonin can interact.

According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 17% of hospitals report at least one pre-op medication error every month. Most are preventable. Your attention to detail saves lives.

What to Expect After the Medication

After the pre-op meds kick in, your child will likely be drowsy, quiet, and maybe a little wobbly. They might not recognize you right away. That’s normal. The medication causes temporary amnesia.

Don’t panic if they don’t cry when you leave. That’s a good sign. They’re not in distress-they’re sedated. You’ll be called to the recovery room when they’re awake and stable. Recovery time varies: midazolam wears off in 1-2 hours; ketamine can take longer, especially if they had emergence delirium.

After surgery, some kids are groggy or clingy for a day or two. A few may have nightmares or refuse to go to bed. That’s common and usually fades. If it lasts more than a week, talk to your pediatrician.

Final Checklist Before Surgery Day

Use this as your last-minute guide:

- ✅ Confirmed fasting times (solid foods, milk, breast milk, clear liquids)

- ✅ List of all medications-brought in writing

- ✅ Pre-op medication instructions printed or saved on phone

- ✅ Comfort items packed (blanket, toy, favorite book)

- ✅ Emergency contact numbers and insurance card ready

- ✅ Questions written down to ask the anesthesiologist

Remember: You’re not just preparing your child-you’re preparing the whole team. Your clarity, calm, and attention make the difference between a smooth procedure and a stressful one.

Can I give my child a pacifier before pre-op medication?

Yes, if your child uses one regularly. Pacifiers can reduce anxiety and provide comfort before sedation. Just make sure it’s clean and approved by the nursing staff. Some hospitals may ask you to remove it right before the medication is given to avoid choking risks.

What if my child vomits after taking the pre-op medicine?

Call the hospital immediately. If vomiting happens after the medication is given, they may delay or reschedule the procedure to reduce aspiration risk. Don’t try to give more medicine or force fluids. Stay calm and follow their instructions.

Is it safe to give my child Benadryl before surgery?

No. Over-the-counter antihistamines like Benadryl can interfere with anesthesia and increase the risk of side effects like drowsiness, breathing problems, or seizures. Always check with your anesthesiologist before giving any non-prescribed medication.

Why can’t I use orange juice as a clear liquid?

Even though orange juice looks clear, it contains pulp and natural fibers that slow stomach emptying. The 2-hour fasting rule for clear liquids only applies to fluids that leave the stomach quickly. Pulp can remain in the stomach and increase the risk of aspiration during anesthesia. Stick to water, apple juice without pulp, or Pedialyte.

How long does the pre-op medicine last?

Oral midazolam lasts about 1-2 hours after the procedure ends. Ketamine’s effects can last longer-up to 4 hours-and may cause temporary confusion or agitation as the child wakes up. The goal isn’t to keep them asleep, but to keep them calm during the transition into anesthesia. Most kids are fully alert within a few hours after surgery.

clarissa sulio

February 2, 2026 AT 08:21Ansley Mayson

February 2, 2026 AT 20:04Bob Hynes

February 4, 2026 AT 05:44Marc Durocher

February 4, 2026 AT 17:18Nick Flake

February 5, 2026 AT 12:12Akhona Myeki

February 6, 2026 AT 15:16Chinmoy Kumar

February 8, 2026 AT 01:51Bridget Molokomme

February 9, 2026 AT 15:43Vatsal Srivastava

February 11, 2026 AT 12:04phara don

February 11, 2026 AT 17:52Hannah Gliane

February 13, 2026 AT 12:27Murarikar Satishwar

February 14, 2026 AT 14:36Dan Pearson

February 15, 2026 AT 19:31