Parkinson’s Disease and Antipsychotics: How Certain Medications Worsen Motor Symptoms

When someone with Parkinson’s disease starts seeing things that aren’t there-people in the room, shadows moving, or loved ones talking to them-it’s terrifying. These hallucinations and delusions are part of Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), affecting nearly one in four patients. But treating them isn’t simple. Many antipsychotics, the very drugs meant to calm these symptoms, can make the shaking, stiffness, and slow movement of Parkinson’s dramatically worse. In fact, using the wrong antipsychotic can turn a person’s life upside down overnight.

Why Antipsychotics Make Parkinson’s Worse

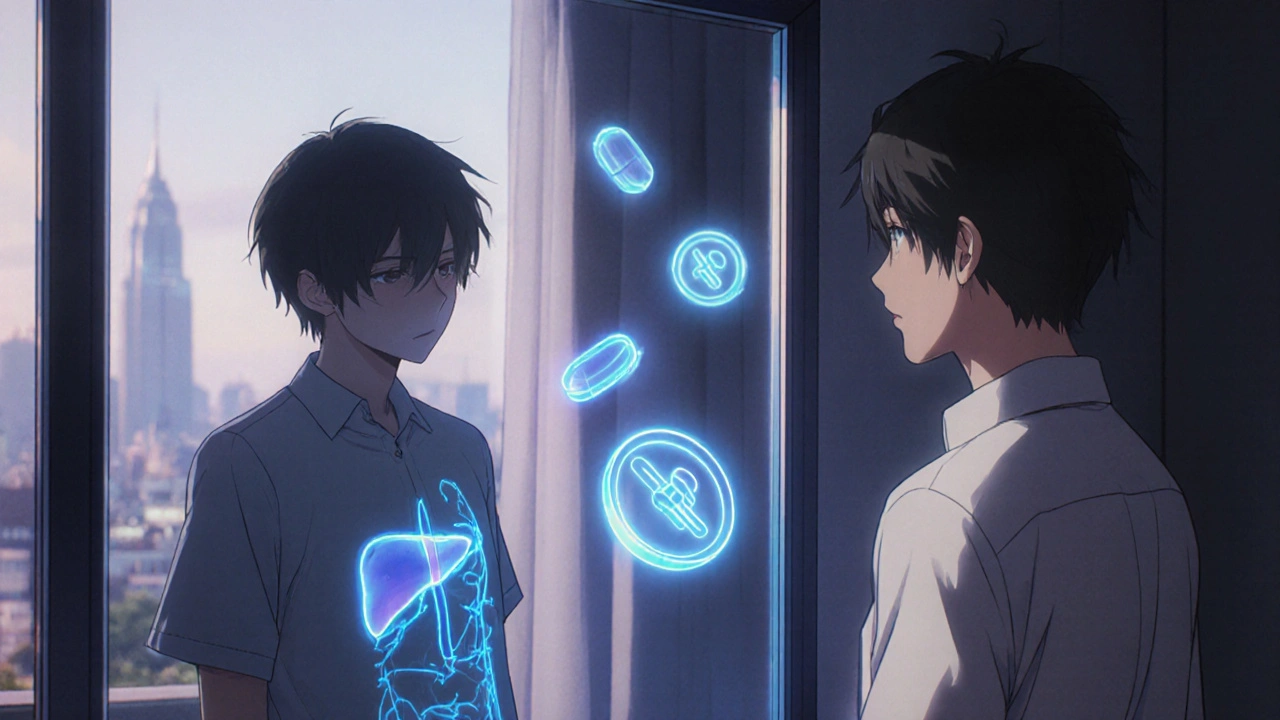

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. Dopamine is the chemical that helps control movement. When it drops too low, you get tremors, rigidity, and trouble starting to walk or speak. Antipsychotics, on the other hand, work by blocking dopamine receptors-especially the D2 type-to reduce hallucinations and delusions in conditions like schizophrenia. But in Parkinson’s, there’s already not enough dopamine. Blocking what’s left is like turning off the last few drops of water from a nearly empty tank. This isn’t just theory. In the 1970s, doctors noticed that patients with Parkinson’s who were given antipsychotics for psychiatric symptoms often became far more immobile. By the 1990s, the American Academy of Neurology had issued formal warnings. Today, we know the mechanism is precise: drugs with high D2 receptor affinity cause the most motor decline. Haloperidol, a first-generation antipsychotic, blocks 90-100% of D2 receptors at standard doses. That’s why it’s considered one of the most dangerous drugs for Parkinson’s patients-even at 0.25 mg a day, it can trigger severe parkinsonism.The Worst Offenders: First-Generation Antipsychotics

First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) like haloperidol, fluphenazine, and chlorpromazine are largely off-limits for Parkinson’s patients. Studies show haloperidol causes motor worsening in 70-80% of cases. In one 1999 study, 75% of Parkinson’s patients on olanzapine (a second-generation drug) saw their psychosis improve-but 75% also got significantly more rigid and slower. Half of them had such a bad drop in mobility that they had to stop the drug. Risperidone, another second-generation antipsychotic, is equally risky. A 1997 study found that every single Parkinson’s patient given risperidone experienced motor decline. Even when lower doses were tried, the risk remained. A 2005 double-blind trial compared risperidone and clozapine head-to-head. Both reduced psychosis equally well. But risperidone caused a 7.2-point increase on the motor scale of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-III). Clozapine? Just a 1.8-point rise. That’s not just a difference-it’s a dangerous gap. And the risks go beyond movement. A 2013 Canadian study found that risperidone nearly doubled the risk of death in Parkinson’s patients. The hazard ratio was 2.46. That’s not a small concern. It’s a red flag.The Safer Options: Clozapine and Quetiapine

There are two antipsychotics that don’t routinely wreck motor function: clozapine and quetiapine. They have lower D2 receptor affinity-only 40-60%-and they also act on serotonin receptors, which helps balance out the dopamine blockade. Clozapine is FDA-approved specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis since 2016. It’s effective, and unlike other antipsychotics, it doesn’t increase mortality risk in this population. But clozapine has its own problem: it can cause agranulocytosis, a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients need weekly blood tests for the first six months. If the absolute neutrophil count falls below 1,500 cells/μL, the drug must be stopped. Still, for many, this risk is worth taking. A 2017 Cochrane Review confirmed clozapine’s superiority over other antipsychotics in preserving motor function. Quetiapine is used off-label because it lacks formal FDA approval for PDP, but it’s widely prescribed. It works faster than clozapine-often within days-and doesn’t require blood monitoring. But its effectiveness is debated. A 2017 study found quetiapine performed no better than placebo on psychosis scales. Still, many clinicians report real-world benefits, especially when used at low doses (12.5-25 mg at night). The key is starting low and going slow.

What About Newer Drugs Like Pimavanserin and Lumateperone?

In 2022, the FDA approved pimavanserin (Nuplazid) as the first antipsychotic for Parkinson’s psychosis that doesn’t block dopamine at all. It targets serotonin 5-HT2A receptors instead. In clinical trials, it improved hallucinations without worsening motor symptoms. That’s huge. But post-marketing data revealed a 1.7-fold higher risk of death compared to placebo. The FDA added a black box warning. It’s an option-but not without serious risks. Lumateperone, currently in late-stage trials, shows more promise. Early results from the HARMONY trial suggest it reduces psychosis by 3.4 points on the symptom scale with almost no motor decline. Final data is expected in mid-2024. If confirmed, it could become the first truly safe antipsychotic for Parkinson’s patients.The Real Solution: Avoiding Antipsychotics Altogether

The best way to treat psychosis in Parkinson’s? Sometimes, don’t use antipsychotics at all. A 2018 study found that 62% of patients who had their Parkinson’s medications adjusted-by reducing anticholinergics, lowering dopamine agonists, or tweaking levodopa-saw their hallucinations disappear without any antipsychotic. Psychosis in Parkinson’s isn’t always a standalone problem. It can be triggered by too much dopamine medication, sleep deprivation, infections, or even dehydration. Before reaching for an antipsychotic, doctors should check for these reversible causes. A thorough medication review is often all it takes.

How to Manage This Safely

If antipsychotics are truly necessary, follow this sequence:- Rule out infections, dehydration, sleep issues, or medication overuse.

- Reduce or eliminate anticholinergics, amantadine, and dopamine agonists if possible.

- Adjust levodopa carefully-sometimes lowering the dose helps psychosis without making movement worse.

- If psychosis persists, start with clozapine at 6.25 mg nightly, increasing slowly over weeks.

- Or use quetiapine at 12.5-25 mg nightly, watching for any decline in mobility.

- Monitor UPDRS-III scores every two weeks. If motor symptoms worsen by more than 30%, stop the drug.

What Patients and Families Should Know

If your loved one with Parkinson’s starts seeing things that aren’t real, don’t rush to the pharmacy. Talk to their neurologist. Ask: Could this be caused by a medication I’m already taking? Have we tried lowering dopamine drugs first? Is there a safer alternative to haloperidol or risperidone? Many families are told, “This is just part of the disease,” and accept worsening mobility as inevitable. But it’s not. The right approach can preserve both mental clarity and movement. The goal isn’t to eliminate every hallucination-it’s to keep the person safe, stable, and able to walk, talk, and live.Final Thought: Balance, Not Just Control

Treating psychosis in Parkinson’s isn’t about finding the strongest drug. It’s about finding the least harmful one. The brain is a tightrope. Too little dopamine, and you can’t move. Too much, and you see things that aren’t there. The answer isn’t more drugs. It’s smarter choices, careful monitoring, and knowing when not to treat.Can antipsychotics cause Parkinson’s symptoms in people who don’t have it?

Yes. Certain antipsychotics, especially first-generation ones like haloperidol, can cause drug-induced parkinsonism in people without Parkinson’s disease. This happens because they block dopamine receptors in the brain’s motor control areas. Symptoms like tremors, stiffness, and slow movement can appear within days or weeks of starting the drug. These symptoms usually improve after stopping the medication, but in some cases, they can persist for months or even become permanent.

Is it safe to use quetiapine for Parkinson’s psychosis?

Quetiapine is commonly used off-label for Parkinson’s psychosis and is generally safer than other antipsychotics because it has low dopamine-blocking effects. However, studies show mixed results-some patients benefit, others don’t. It’s not FDA-approved for this use, and a 2017 trial found it worked no better than a placebo. Still, many doctors prescribe it at low doses (12.5-25 mg at night) because it’s well-tolerated and doesn’t require blood monitoring. Always monitor motor function closely when starting it.

Why is clozapine considered the gold standard despite its risks?

Clozapine is the most effective antipsychotic for Parkinson’s psychosis with the least motor side effects. Unlike other drugs, it doesn’t significantly worsen tremors or slowness. It’s also the only one with FDA approval specifically for this use. The main risk is agranulocytosis-a rare but life-threatening drop in white blood cells. Because of this, weekly blood tests are required for the first six months. But for patients who respond, the benefits often outweigh the risks, especially when other options have failed.

What should I do if my loved one’s motor symptoms suddenly get worse after starting an antipsychotic?

Stop the medication immediately and contact their neurologist. Sudden motor decline after starting an antipsychotic is a red flag, especially with drugs like haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine. Don’t wait to see if it gets better. Document the timeline-when the drug started, when symptoms worsened-and bring all current medications to the appointment. The neurologist may need to reverse the drug effect and switch to a safer option like clozapine or adjust Parkinson’s medications instead.

Are there non-drug ways to manage psychosis in Parkinson’s?

Yes. Many cases of psychosis in Parkinson’s are triggered by reversible factors: sleep deprivation, urinary tract infections, dehydration, or too much dopamine medication. Improving sleep hygiene, treating infections, adjusting levodopa timing, and reducing anticholinergics can resolve hallucinations without any antipsychotic. Environmental changes-like adding more lighting, removing mirrors, or reducing noise-can also help reduce visual hallucinations. A 2018 study showed that 62% of patients improved with medication adjustments alone.

Kartik Singhal

November 22, 2025 AT 02:24So let me get this straight - we’re giving people with Parkinson’s drugs that block dopamine… while their brains are already crying for more? 🤦♂️ This isn’t medicine, it’s a biological slap in the face. They should just let nature take its course and call it a day. Or better yet - ban all antipsychotics and blame the patients for ‘seeing things’.

Logan Romine

November 23, 2025 AT 12:17Wow. So we’ve turned brain chemistry into a Jenga tower and someone just pulled the dopamine block. Now we’re surprised the whole thing collapsed? 😏 The real tragedy isn’t the drugs - it’s that we still think ‘more control’ means ‘better outcomes.’ Maybe the answer isn’t tweaking neurotransmitters… but learning to sit with the chaos. 🌌

Anne Nylander

November 25, 2025 AT 09:10OMG this is so important!! I had my dad on risperidone and he went from walking to barely moving in 3 days 😭 We didn’t know any better. Thank you for writing this!!

Chris Vere

November 27, 2025 AT 00:15The medical establishment has long treated the mind as separate from the body. This is a perfect example of that error. Dopamine is not merely a chemical signal; it is the bridge between intention and motion, between perception and reality. To disrupt it recklessly is to sever the self from its own expression. We must proceed with reverence, not reduction.

Paula Jane Butterfield

November 27, 2025 AT 22:45As a nurse who’s worked with Parkinson’s patients for 20 years, I’ve seen this over and over. Families panic when hallucinations start and beg for meds. But 7 out of 10 times, it’s just too much levodopa or a UTI. We forget to check the basics. This post? Gold. Please share it with every neurologist you know.

Corra Hathaway

November 28, 2025 AT 13:46So… we’re saying the safest antipsychotic is the one that doesn’t exist? 😅 Pimavanserin has a black box warning. Clozapine needs blood draws every week. Quetiapine might as well be sugar pills. So what’s left? Hope? 😔 I just want my mom to see me clearly… not a ghost. But I don’t want her stuck in a chair either. This is the worst kind of no-win.

Leo Tamisch

November 29, 2025 AT 21:10Let’s be real - this entire field is just pharmaceutical theater. We don’t treat psychosis in Parkinson’s. We treat profit margins. Clozapine? Too messy. Pimavanserin? $30k/year. Quetiapine? Off-label and cheap. The system doesn’t care if you can walk - only if you can pay. 🤑

Sandi Moon

November 30, 2025 AT 00:06One must wonder: if these drugs are so dangerous, why are they still prescribed? Is it ignorance? Or is it something darker? The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has spent decades conditioning clinicians to reach for the pill first - even when the pill is a scalpel to the spine. The truth? They’d rather control the mind than preserve the body. And if you question it? You’re just another ‘conspiracy theorist’.

Franck Emma

November 30, 2025 AT 19:56My brother died after they gave him haloperidol. He stopped eating. Stopped talking. Just… froze. They said it was ‘progression.’ It wasn’t. It was murder by prescription. I hope this post burns down every pharmacy that stocks it.

Eliza Oakes

December 1, 2025 AT 02:34Wait - so quetiapine doesn’t work better than placebo? Then why do half the neurologists still prescribe it? Are they just lazy? Or is it because they don’t want to deal with clozapine’s blood tests? This whole system is broken. Someone’s getting paid to keep this going.

Mark Kahn

December 1, 2025 AT 09:10You’re not alone. I’ve been there. My wife started seeing people in the hallway. We panicked. But after we cut her anticholinergics and adjusted her levodopa? The visions faded in 48 hours. No drugs needed. It’s not magic - it’s just science you didn’t know existed. Don’t give up. Talk to a specialist who actually knows Parkinson’s.

Shawn Sakura

December 2, 2025 AT 17:44As a caregiver, I want to say THANK YOU for writing this. My mom’s neurologist didn’t even know about pimavanserin. We found out on our own. It’s scary how little most doctors know. Please keep sharing this. I’ll send it to every support group I’m in. We need more awareness. ❤️

Clifford Temple

December 3, 2025 AT 20:28Why are we letting Big Pharma dictate brain health? This is why America’s healthcare is a joke. In Germany, they’d never prescribe risperidone to someone with Parkinson’s. We’re behind. We need to ban these drugs outright. And stop letting corporations profit off broken brains.

Noah Fitzsimmons

December 4, 2025 AT 06:11Oh so now we’re blaming the system? Cute. You think the patients didn’t have choices? They signed consent forms. They got counseling. They were warned. If you’re too scared to use clozapine, don’t blame the doctors. Blame yourself for not being brave enough to face the risk. Real medicine isn’t safe. It’s necessary.